12 January 1964 on ABC Weekend TV

A deep dive into a typical ABC Sunday in 1964

★

We start the day with an hour of adult education. There were no advertisements in or between these programmes, making the viewing experience something like watching BBCtv. So why did Independent Television bother? The answer is twofold. First, it was very good politically: when MPs and the great and the good stood up to decry television in general and ITV in particular, as they did with wearisome regularity, it was very helpful to point to these educational and highbrow offerings as a way of deflecting criticism of Crossroads and Double Your Money. The second reason was to do with advertisement placement on the network.

The number of minutes each hour and each day allowed for advertising was severely limited by the Postmaster General. An hour of programmes that didn’t count towards the maximum hourage of television permitted each day but did count towards the average number of hours for calculating permitted advertisement time allowed the ITV companies to sell a couple of minutes more during peak time, which more than paid for the programmes themselves.

Another reason was to do with the post-war settlement. The people behind television had been through the Second World War and had joined the rest of the country in deciding that the nation needed drastic change once the conflict was over. This came through universal free healthcare, social security, decent affordable housing, and a new view of education as something that was a right for children and a responsibility for government. The school leaving age was progressively raised, technical colleges created to ensure that future manual workers could get qualifications and a university education became something obtained through hard work and intelligence rather than access to lots of money and who your father knew.

But what about those who had already left school? And those that had slipped through the cracks in the system? The television executives thought they could do their bit by providing programmes for anybody who wanted to learn more, even as they sat at home with 45 hours of work bearing down on them from tomorrow. And they were right: millions watched, thousands learnt and hundreds went on to do night classes or even go back to education. ITV may have benefited from the reputation boost and the income from these programmes, but it’s important to remember the genuine altruism of the executives in a time of a more communal nation state.

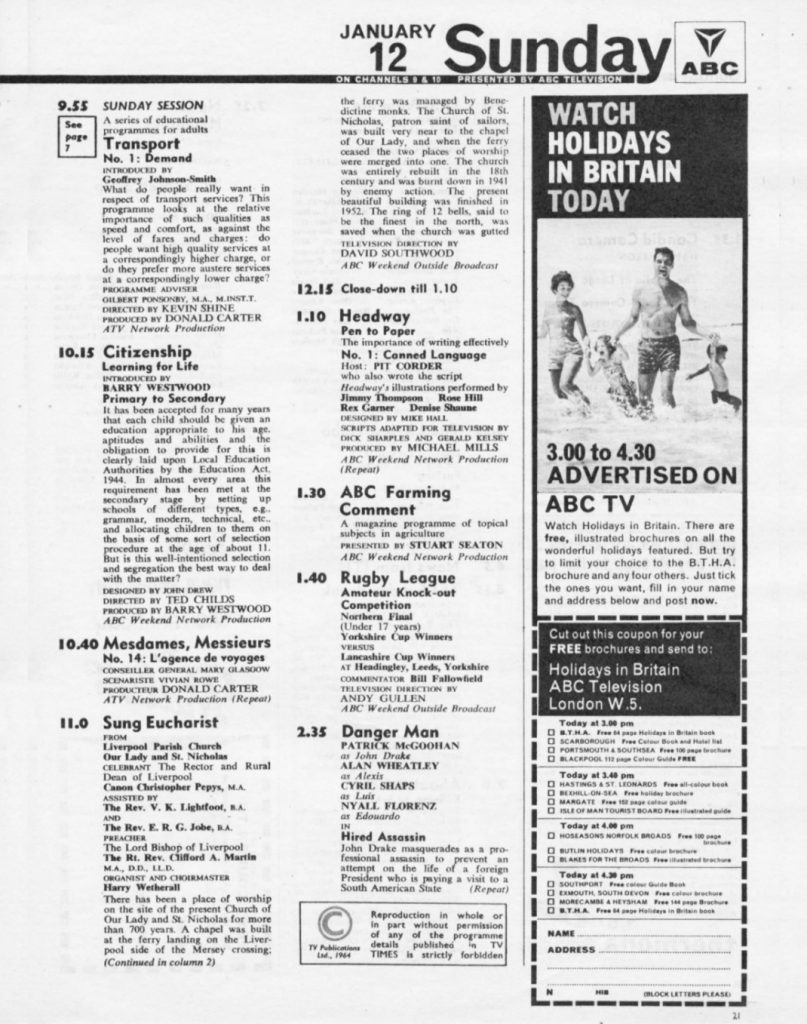

Transport (9.55am) From the timing of this programme, you would be forgiven for thinking that it’s going to be based on the Beeching Report of 9 months earlier. While that was undoubtedly fresh in people’s minds – especially if they were about to lose their local rail service – the programme is actually more subtle than that.

What it is actually about is teaching reasoning and explaining that political and personal decisions often require a balance to be made between two competing but mutually exclusive goals – in this case, high quality services vs low fares. Both are laudable goals. But we can’t have them together. Which should we chose? Is there a balance between these two societal goods? What appears to be a programme about rail and bus journeys is, therefore, actually a complex lesson in sociology and a window into the world of high-level decision making.

Citizenship (10.15am) The 1944 Education Act, implemented by the incoming post-war Labour Government, extended free secondary education to the masses, most of whom had previously left formal education at 14. But the method it used was becoming controversial. Each child did a series of tests at age 11, which divided them into three: the ‘gold’ children, the brain boxes, who could deal with intangibles and would go on to grammar school and thus into management positions; the ‘silver’ children, who needed solid notions, who could be taught what they needed to know for their skilled and semi-skilled apprenticeships, plus enough maths to do the shopping and enough English to write a letter in secondary schools; and the ‘iron’ children, who you couldn’t educate in such a way, who would learn to do things with their hands in the technical schools, ready for their manual jobs.

It was thought that a third of all children would go into one of the three streams, and a third of the budget would follow them. In practice, 25% of children went to grammar schools and 75% went to secondary schools – the technical schools were usually simply not built. Worse, 75% of the money went to the grammar schools and 25% to the secondaries.

The result was seen to be that most middle class children got the grammar school education they’d always got, but now for free, whilst most working class children were taught the basics en masse and thrown into the job market. The upper class children continued as they had before, in private schools. This did nothing at all for Britain’s rigid class structure: at 11 years old, children were told whether they were upper, middle or working class and that was that – there was to be no movement between the three tiers.

By 1964, there was a groundswell against this system, especially (but not exclusively) in the opposition Labour Party. They had swept the municipal elections the previous year and were now pursuing a policy of ‘comprehensivisation’ in Bristol, Manchester, Liverpool and London – creating mixed schools where all pupils would go at 11, allowing for pupils to move between streams, mix with different classes, and, most importantly, benefit from 100% of the total budget.

So why this programme? It’s not really to explain all that we’ve just said, although it did do that. Like Transport before it, it was again teaching reasoning and sociology, and again showing that decision making, especially at a high level, was about balancing competing priority and social goods: in this case, teaching children according to their needs vs teaching children according to the nation’s future needs. It also served to explain how children were being educated to their parents – this period is before Parent/Teacher Nights and report cards being sent home, an age when parents sent their children to school to be educated and simply expected that to happen without much in the way of the real-time measurement and micromanagement that is now the norm.

Mesdames, Messieurs (10.40am) The programmes companies often specialised in certain types of programmes. In schools television, Rediffusion did a lot of French teaching programmes; in adult education, ATV did the same. Most interesting was Tyne Tees, which specialised in Russian. A nice touch from the TVTimes is putting the credits of Mesdames, Messieurs in French.

Closedown (12.15pm) Everything stops for Sunday lunch, which includes television and even the transmitters: the plugs at Winter Hill and Emley Moor being pulled and the staff going off for dinner. Meanwhile at ABC in Parrs Wood Road, Didsbury, the staff would stream out across the road to the Parrs Wood pub for a carvery and a swift half.

Headway (1.10pm) We’re back on air for more adult education. This one is disguised as a “how to write better letters” programme, but was actually more subtle than that: it was about how to write letters, full stop. Much of the pre-Butler Act population had left school at 14, as mentioned above, and, whilst not illiterate, they were awkward with writing long pieces and had poor penmanship skills.

This programme therefore taught them how to write cursive, where to put the name and address, how to start and finish – the basics that we, educated to 16 and beyond, would now take for granted. The title ‘Headway’ originally applied to all of ABC’s adult education output, and was a series of series on different subjects, including basic cooking skills with Philip Harben.

The strand had outgrown the ‘Headway’ branding and expanded in the year since networked adult education programmes began on ITV, but the name was in the titles of the original series so was kept on as they were regularly repeated – this one being almost exactly a year old having launched the Sunday Session slot.

ABC Farming Comment (1.30pm) We think of ABC as serving the industrialised north of England and the factory lands of the west Midlands. But their VHF transmissions went much further, with Winter Hill penetrating into the north of Wales, Emley Moor covering Lincolnshire and Lichfield reaching into Herefordshire and Worcestershire.

These areas had less population than the cities ABC also covered, but were economically important. A programme of interest to farmers sold advertising either side heavily – Monsanto, the maker of DDT, was a big customer for these slots – making it a very worthwhile programme for ABC. Despite only being 10 minutes, including the advert breaks either side, it was packed with features made by the ABC Outside Broadcasting unit during the preceding week, as well as having Stuart Seaton, founding editor of the Farmers Guardian, commenting on the latest agricultural news.

Rugby League (1.40pm) General entertainment programming on Sundays had been restricted by the Postmaster General to not starting until 3pm. This had just been loosened to “not starting until after 2.30pm”.

This ‘after’ had bothered the ITV companies, but rather than seeking clarification, they went for 2.35pm as the start of entertainment programming. That leaves ABC with just short of an hour to fill with something that must be clearly for a minority audience.

Here they fill it with Rugby League football, the northern version of the game for men with odd-shaped balls. Thus ABC wins by showing something that’s both popular in their area but a minority pursuit in the UK as a whole, neatly sidestepping the rules.

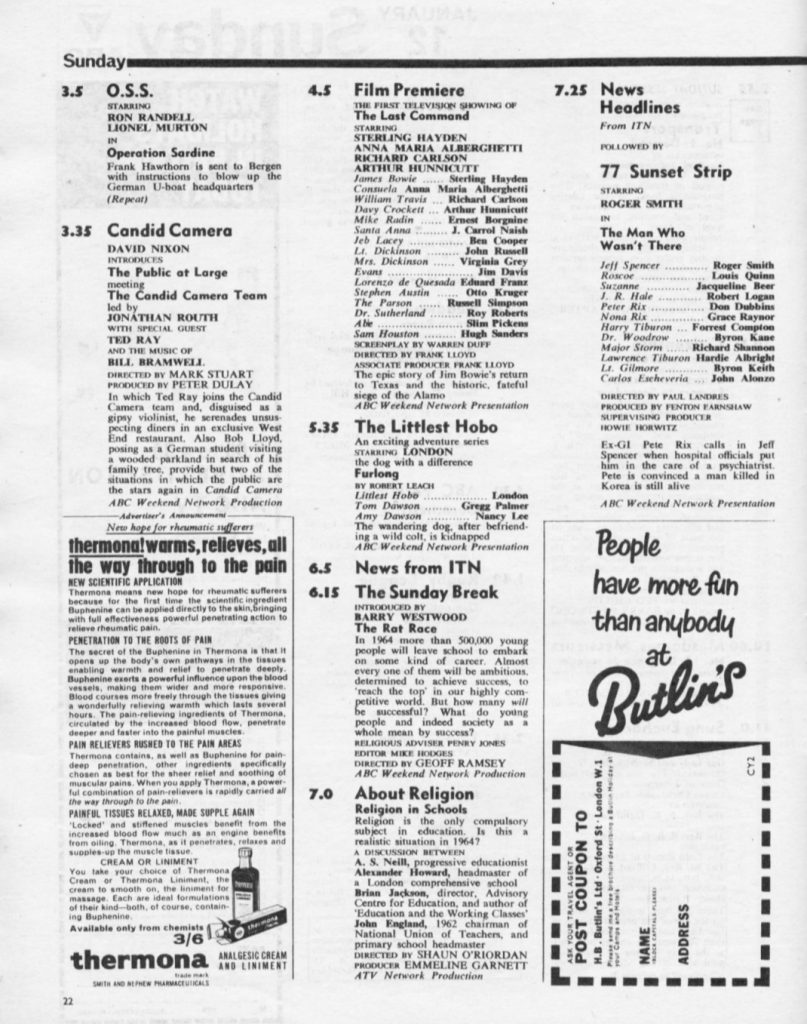

Candid Camera (3.35pm) The Independent Television Authority loathed Candid Camera from the beginning in 1960. The first two editions were presented by Bob Monkhouse who then fled, not returning for the full run starting in 1961.

It was perceived as nasty, even cruel, with the public as victims who were being laughed at, not with. The ITA hated this, and looked for reasons to ban it. There were none, besides the Authority requiring that it saw written permission from everyone who appeared in shot to prove they were happy to be seen. But by and large they were, so that didn’t work.

Nevertheless, ABC and the TVTimes work hard here to soften the programme in the description. The public aren’t victims, they’re the stars. David Nixon, always avuncular, gives the show a soft, happy narration, encouraging us to laugh with the victims, err, stars, rather than at them.

When the format was reborn in the 1980s under the eye of Jeremy Beadle at LWT, this was taken a stage further: the victim of the prank was brought into the studio, professionally made-up, given quality clothing and treated like a true star. They appeared in their finery in a box in the corner of the screen as the prank played out, laughing at themselves and the whole scene.

It made for slightly less excruciating viewing. But only slightly.

The Littlest Hobo (5.35pm) This series was based on a 1958 US film, and ran for two seasons of 61 episodes in total. It was made in Canada in colour, being broadcast in Canada and the US in 1963, so this is a pretty recent import for ABC. The programme was revived in 1979, running for 114 episodes over six seasons.

The Sunday Break (6.15pm) Barry Westwood makes his second appearance of the day on ABC. The idea for this programme was conceived of as a way of filling the previously off-air 6.15pm to 7pm period, presented to MPs and churchmen as speaking to people who weren’t going to church anyway, people who took the 45-minute closedown as an opportunity to put on Radio Luxembourg or their collection of 45s.

People who went to church would still go to church, ABC’s argument ran, so here’s a way of reaching those that didn’t, in a format that would speak to younger people in particular. This argument worked, the closedown was abolished, and The Sunday Break appeared and immediately began to undermine the purpose it was created for.

The description says it all: this isn’t religion, despite the presence of Penry Jones as the Religious Adviser, and despite there usually being a (generally young and hip) vicar present on screen. This programme is, yet again, about sociology, this time disguised as moral questions. 1964 really was a time when everybody was a budding sociologist, with big plans for the future of the nation and the world – this fed directly into the White Heat of Technology ethos that would bring Harold Wilson’s Labour party back into power after 13 years in October.

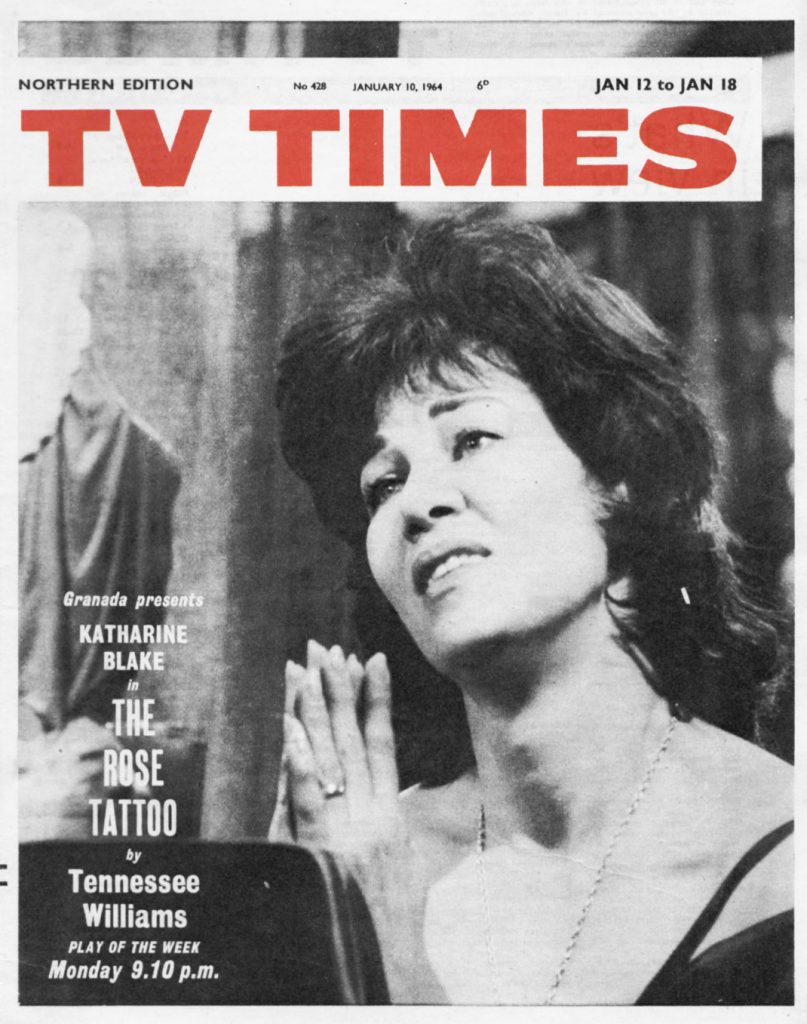

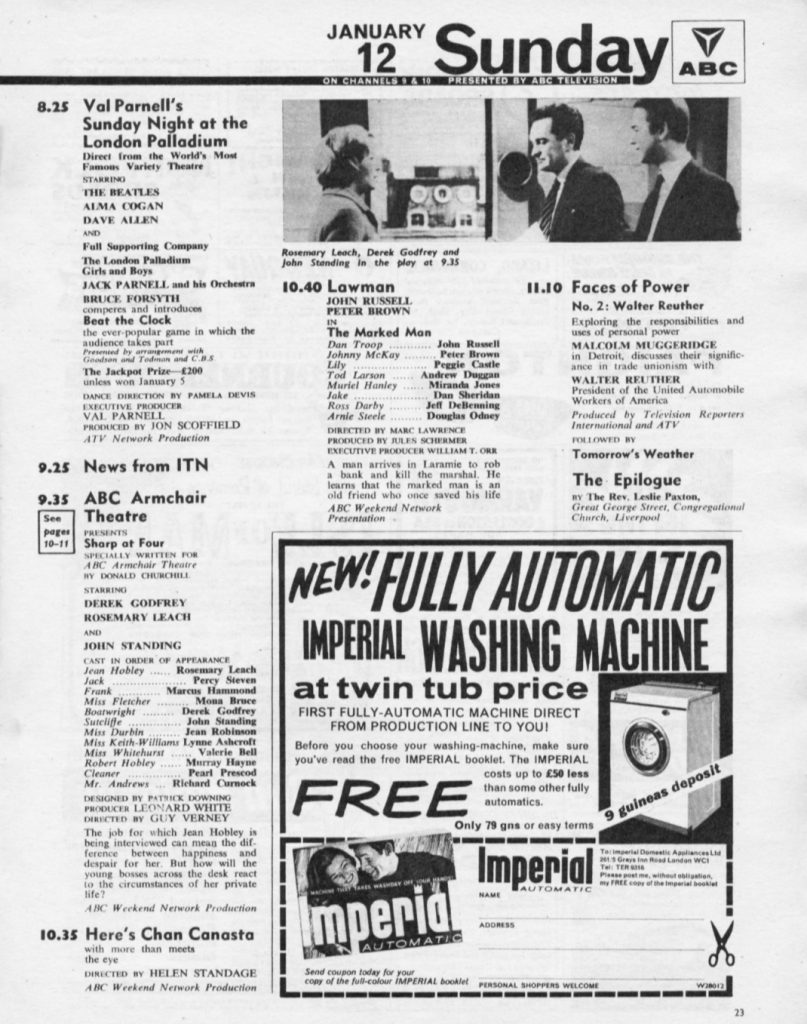

Val Parnell’s Sunday Night at the London Palladium (8.25pm) Here we are in the last few months of The Beatles still being a British phenomena, with Beatlemania in the US coming shortly but not yet sparked off. Therefore, they’re still available to appear on the Palladium show in a way they wouldn’t be in a year’s time; just a year before, they were still to be found on Granada’s local news magazine Scene at 6.30.

Meanwhile, Alma Cogan was going in the other direction: a year before she had been too big for the Palladium; a year later she’d be lucky to get on About Anglia. Although she didn’t know it – her family decided not to tell her – she was already dying of stomach cancer. It would kill her in October 1966.

ABC Armchair Theatre (9.35pm) Women had been a power in the workforce during the recent war, but when the men came home from the front, Jill was supposed to get back in her box.

And for much of the 1950s, she did. But things were changing. Single women were now an important part of working life, if only because there was a drastic labour shortage. But married women? No, they were expected to leave their jobs after the wedding and get on with being housewives.

The world in 1964 is moving on: divorce has got easier, but what about divorced women? The ex-husband was often, but by no means always, told by the court to contribute to any child’s financial wellbeing. Divorced women, however, were expected to support themselves… but how? Employers were used to women leaving upon marriage and thus had no experience of hiring people with childcare obligations, since men never had any.

Armchair Theatre had been revolutionary since it began, showing the millions of ITV viewers such issues as ‘the colour bar’, addiction, literacy, even hinting at the ‘problem’ of homosexuality. Here Donald Churchill takes this new issue in hand: what do we do about a divorced woman with childcare responsibilities who needs money and wants to work? As an aside: why, 56 years later, is this still an issue?

Faces of Power (11.10pm) Here’s a programme with three uses. First, it’s an export sale for ATV, clearly aimed at being sold to NET, the American public broadcasting network.

Secondly, it counts for the ITA as a ‘serious’ contribution by ATV, always useful for a company permanently accused of being too lightweight and entertainment-driven.

Thirdly, it’s useful for ABC, who have had 7 hours and 25 minutes on air today with programming that counts towards their 15 hour maximum for the entire weekend. With the adult education in the morning, the OB from Headingley in the afternoon and all the religion excluded, the hours of entertainment have rapidly added up. But who wants to go off air at about 11.15pm if they can help it? Certainly not ABC. A half hour of further adult education takes them much nearer to a more useful closedown time.

Epilogue (untimed) We’ve pointed this out before elsewhere, but the epilogue ran 7 nights a week in the Midlands, across both ATV and ABC. In the North, Granada had no interest in any religious programming unless they scored a Christmas Day on a weekday, and even then the reluctance was palpable.

Therefore tonight’s epilogue is one of only two seen in the North in an average week. When they came from Aston, the vicar presenting would sometimes slip up and tell viewers what he’d be talking about tomorrow, despite not appearing on Granada.

Tonight, he’s in the North, most likely in ABC’s tiny remotely operated single camera studio on the top floor of the ABC Forum cinema on Lime Street in Liverpool. He’ll need to pull a cord to switch off the lights and camera when he leaves.

About the author

Kif Bowden-Smith is the founder of the Transdiffusion Broadcasting System. Russ J Graham is the editor-in-chief.

Thanks Kif,a great read…

Thanks Ray! There’s another ABC TVT article arriving on ZENITH next week. Do come back!

I’m suddenly 13 years old again… thank you both for another great insight into ‘the year that changed everything’.

And I’ve learnt something… I never knew that ABC had a remote cubby hole atop the Forum in Lime Street!

Thanks Pete! I’m always trying to emphasise that ABC were of more cultural substance than a certain other pre 1968 weekend franchise!!! ????

There’s another ZENITH – ABC TVT review article next week too! Do come back!

I discovered that the Canadian series The Littlest Hobo (1963) was originally filmed in colour, when I purchased a 2 DVD Region 1 set from Amazon.

We forget how tightly regulated and controlled broadcasting hours on a Sunday were back in 1964. Hard work for ITV companies to make sure they have accounted for every minute on air, and try and use the exempted programming genres to expand their day and get a little bit more ad revenue. Hard work.